Heaven’s gate … visitors approaching the entrance to the new complex, designed to look like a 13th-century village

Heaven’s gate … visitors approaching the entrance to the new complex, designed to look like a 13th-century village

We’ve all done it: fetched up somewhere so idyllic on our travels that we hate the thought of going home to stress and normal life.

More than 2,000 years ago, a Chinese wise man, An Ky Sinh, felt this way when he arrived at Yen Tu mountain in northern Vietnam. He had been sent by China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang (259-210BC), conqueror of six warring states and creator of the unified nation. Being such a splendid chap, he thought he deserved to live forever, so ordered his most learned courtiers to travel north, south, east and west and bring back herbs to make him immortal.

This quest brought An Ky Sinh to Vietnam, and the highest mountain in these parts: 1,068-metre Yen Tu, on whose lush slopes there still grow all manner of medicinal plants. Being wise, he knew that whatever potions he concocted the emperor would still eventually die (when he did, he was buried, modestly, with 8,000 terracotta soldiers), and he, An Ky Sinh, would be proved a failure. So he stayed, making his home on this stately peak, with views over lower ranges to the coast, and was revered for his healing skills – if not for cheating death.

The mountain’s reputation was further enhanced when another warrior king, 13th-century Vietnamese ruler Tran Nhan Tong, abdicated and retired to live as a monk on Yen Tu, founding the Truc Lam (bamboo forest) version of Zen Buddhism. Ever since (except for a few decades under communism), millions of Vietnamese Buddhists have made pilgrimages to the mountain’s temples, statues and pagodas, usually around Tet (new year, which started this week).

Pilgrims follow a route past temples and pagodas

Pilgrims follow a route past temples and pagodas

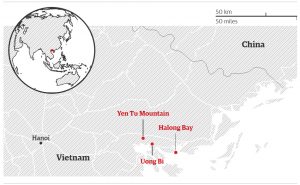

Yen Tu is just off the well-trodden route between Hanoi and Halong Bay, yet a lack of facilities has kept it off most holidaymakers’ radar. Vietnamese pilgrims tend to either make a very early start from Uong Bi city, 17km away, or sleep on mats on restaurant verandas before tackling the four-to-six-hour climb up the mountain. Now though, a new “village” at the foot of Yen Tu is attracting a different kind of traveller, with a design hotel, hostel accommodation and, eventually, 25 shops, restaurants and cafes.

That might sound like building a Butlin’s under Scafell Pike, but it’s not. We arrive in the early evening at a complex that, though brand new, feels centuries old. Low-rise buildings stretch up the slope behind an entrance gate with an ivory bamboo bush in a mirror-like pond. In the lobby of the Legacy Yen Tu hotel, traditional hangings blow in the warm breeze from the Dong Trieu mountains.

Cable cars can take some of the strain; otherwise it’s a climb of at least four hours

Cable cars can take some of the strain; otherwise it’s a climb of at least four hours

I’m keen to get out and tackle Yen Tu’s challenging 6km of steps and steep rocky paths. The climb would take at least four hours on foot, but a typhoon over the South China Sea brings torrential rain so we take a cable car part of the way. I like the mountain’s egalitarian feel: even on the busiest days of Tet, there’s no express booking. Politicians and pop stars queue with everyone else. At a cafe higher up, families are eating pilgrim food – boiled eggs and sweet potatoes.

A bedroom in the Legacy Yen Tu MGallery hotel

A bedroom in the Legacy Yen Tu MGallery hotel

The route replicates the monk-king’s first pilgrimage, with shrines at points where he rested, washed and ate, plus stupas marking his tomb and those of generations more monks.

After stomping around in the damp for several hours, it’s good to get back to the hotel. The development aims to replicate a 13th-century village and is the vision of Bangkok-based architect Bill Bensley – the name behind several acclaimed Asian hotels – and entrepreneur Bui Dinh Tuan. Roofs are gently curved and eaves hang low, to keep the tropical rain out. It feels like the set of a kung fu movie, which is no accident – long, pillar-lined hallways in the hotel are designed for a monastic feel.

The 100-plus hotel rooms are aimed at middle-class Vietnamese, with rice-sack headboards to symbolise plenty and ceramic jars copied from Hanoi’s national history museum. There are handmade tiles, carved wood and stone, and walls speckled with rice bran, a traditional technique for absorbing damp in the wet season.

Blessed sleep … dorm beds in the village lodge have curtains and reading light and cost about £13 a night

But I also love the four-bed dorms (75 eventually, £13 a night) in low-roofed cottages across the three-acre central courtyard. Carved wooden bunks have curtains and a reading light, and each cottage has a veranda. (The really impecunious can stay for free in the on-site monastery, in exchange for work in the gardens.) There’s yoga and meditation for guests, and a pool and spa will open later this year. It’s all aimed at extending the tourist season beyond the new year celebrations (mid-January to March – the hostel is fully booked to 1 April).

At the top of the mountain are two statues: a 15-metre seated bronze of King Tran, and a weathered, shapeless one said to be of An Ky Sinh himself. For me he’s the more important figure. Religion has long been the draw for locals, but the mountain is a special place in its own right, with two major waterfalls, dense bamboo forest, pines more than 700 years old, apricot groves nearly as old (don’t miss the tangy local liqueur), and medicinal plants science is only now learning about.

Halfway up, the One Roof Pagoda, built into the mountainside, houses a spring said to grant drinkers one wish. Mine, for the rain to stop, is not granted. But that’s just as well: if I’d enjoyed this “stairway to heaven” under blue skies, tearing myself away might have been as hard as it was for An Ky Sinh 2,000 years ago.